With 5+ years of experience in branding, I have both designed new logos and refined existing ones. Something that has always fascinated me is the mathematics behind design. Are there certain shapes that are perceived as more balanced, harmonious, and beautiful than others?

The shape most often highlighted in this context is the Golden Ratio. I decided to delve into this mythical proportion to see if, and how, it is used in logo design.

What is the Golden Ratio?

The Golden Ratio is a mathematical ratio believed to create compositions pleasing to the human eye. Usually written as the Greek letter phi (φ), the Golden Ratio is strongly associated with the Fibonacci sequence, where each number is the sum of the two preceding ones.

1 + 0 = 1

1 + 1 = 2

2 + 1 = 3

3 + 2 = 5

5 + 3 = 8

8 + 5 = 13

13 + 8 = 21

21 + 13 = 34

34 + 21 = 55

Interestingly, once the numbers are sufficiently large, starting from about 55 and upward, the ratio between consecutive numbers is always approximately 1.618. The larger the numbers, the more accurate the ratio becomes.

55 / 34 ≈ 1.6176

89 / 55 ≈ 1.6182

144 / 89 ≈ 1.6181

233 / 144 ≈ 1.6180

This size ratio, also known as the Fibonacci Ratio, is often expressed in squares. Here, each square’s side length is 1.618 times larger than the side length of the previous square:

You can also draw a rectangle with a height-to-width ratio of 1.618, resulting in the following shape:

Let’s make it even more interesting by drawing a logarithmic spiral (sometimes referred to as The Golden Spiral) with the growth factor of the Golden Ratio, 1.618. When added to our rectangle, we get the following result:

The Golden Ratio in Art and Nature

The Golden Ratio has been known since 300 BCE, and some suggest we are naturally drawn to it because its proportions appear in nature; for example, in certain shells, leaves, pinecones, and sunflower seed spirals. However, examples that are often used to “prove” the golden ratio is both few, and in many cases not even correct.

One might expect the Golden Ratio and Fibonacci sequence to be ubiquitous if they were so crucial…

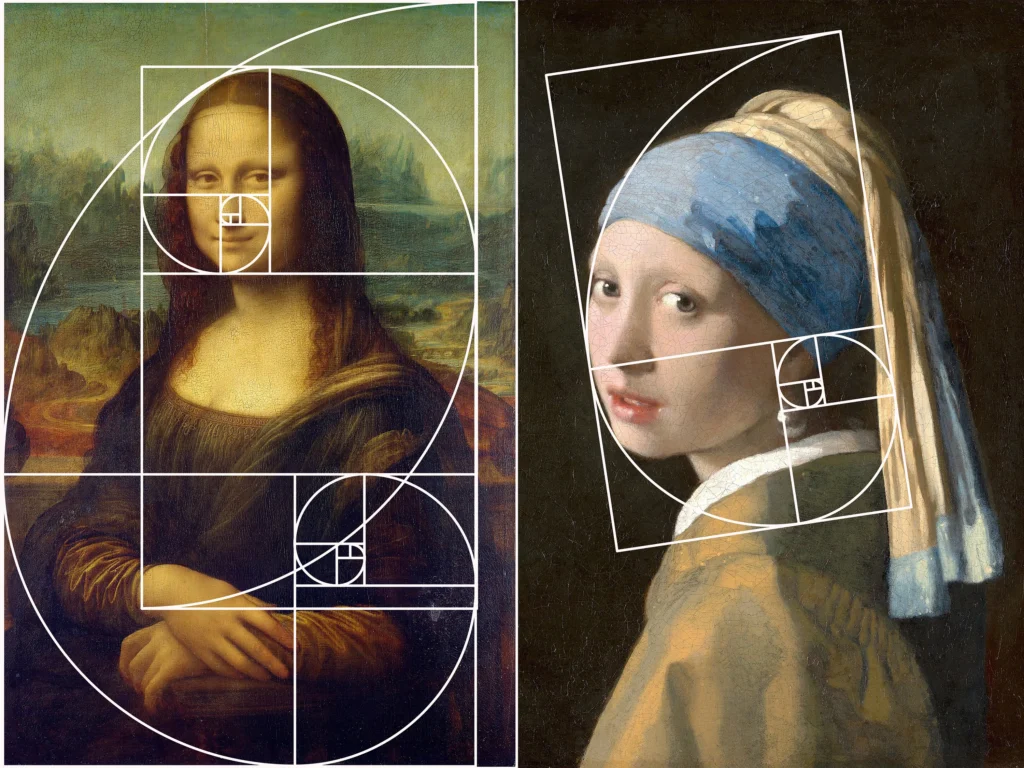

The Golden Ratio is also said to appear in both architecture and art. This is usually demonstrated by overlaying the Golden Ratio on a painting. Using this method you can “reveal” the golden ratio in classical paintings such as Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” (1503–1506) and Johannes Vermeer’s “Girl With a Pearl Earring” (1665):

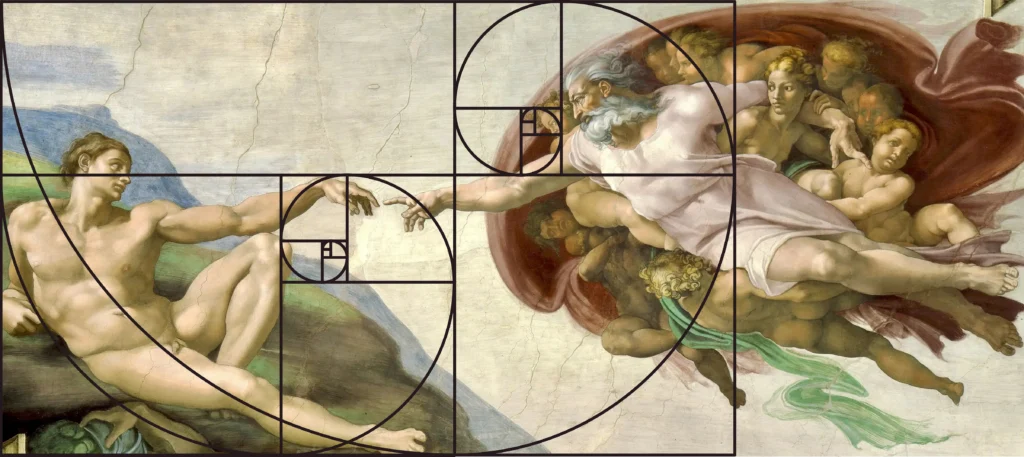

Another masterpiece often associated with the Golden Ratio is Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam” (1510).

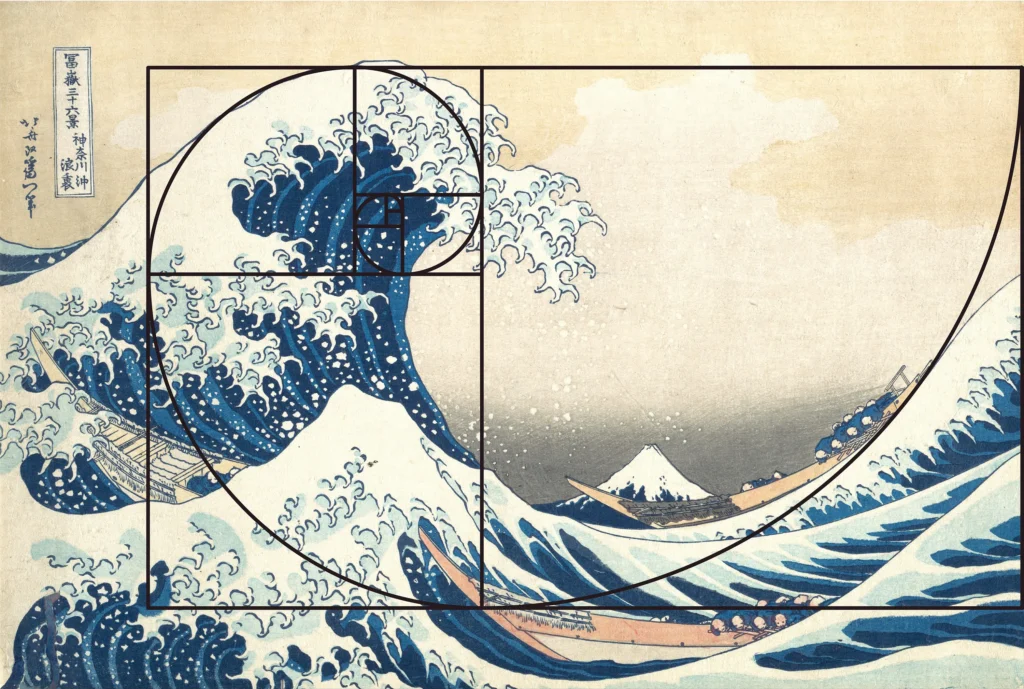

However, much like in nature, one might expect the Golden Ratio to reflect more precisely in art and in many more paintings if it had such aesthetic power, as in “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” (1832).

The Golden Ratio in Logo Design

There is reason to question how significant the Golden Ratio really is and whether it is even perceived as more beautiful than other proportions.

At the same time, the Golden Ratio has become so famous and mythical that it likely inspires and is used by some designers in their process. It can also, of course, appear as a sheer coincidence.

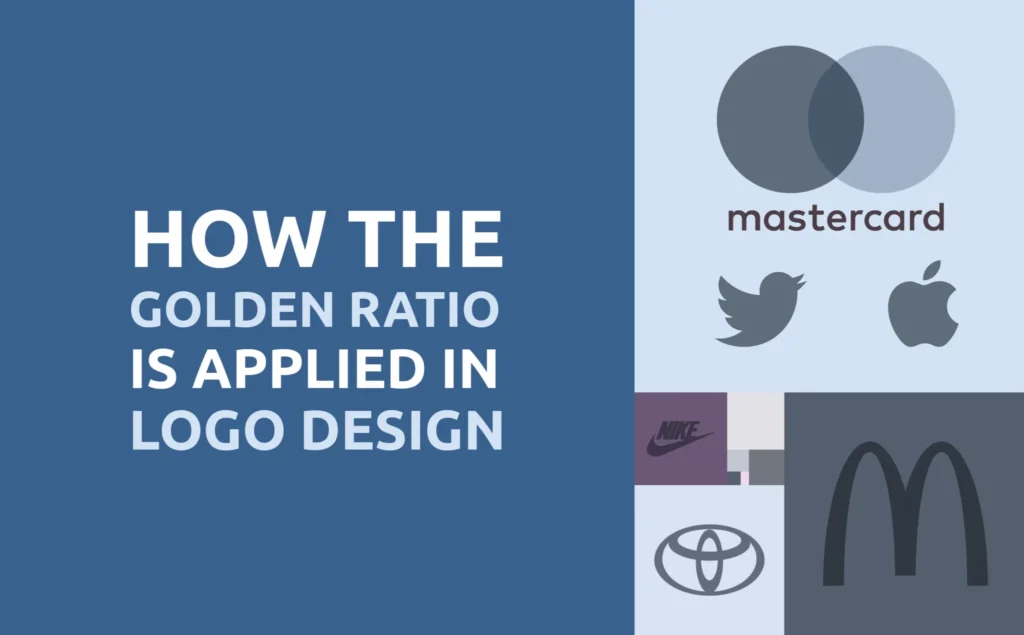

Here are some examples of golden ratio in logo design:

The Golden Ratio is also easy to spot in Nvidia’s eye symbol.

Toyota’s symbol has clear features of the Golden Ratio.

In the Adidas logo, the Golden Ratio is almost perfect.

If we want to be a bit more creative, we can also find the Golden Ratio in McDonald’s Golden Arches, where each arch has a proportion of 1.618.

Golden Ratio Circles in Logo Design

Another way to use the Golden Ratio in logo design is to use it in circles with a radius relation of 1.618.

Mastercard is a perfect example of how two circles are positioned to form the Golden Ratio.

The Pepsi Globe can be drawn with the support from two circles with a relation of 1.618.

Apple’s well-crafted symbol is actually drawn from a multitude of circles with a relation of 1.618. Would the symbol have had the same balance if it were drawn with another ratio?

Twitter’s bird is also a great example of a symbol drawn from circles with a relation that follows the Golden Ratio.

What to Draw From This?

The Golden Ratio is often portrayed as very significant in both nature and art, creating beautiful and balanced proportions. In reality, it is difficult to find clear and indisputable examples where the Golden Ratio prominently appears.

This suggests that the Golden Ratio may not be as crucial as it is often portrayed. Yet, its fame has likely inspired many designers.

When examining existing logos, one can indeed find a number where the proportions seem to match the Golden Ratio. But, as in art and nature, this applies to a very small percentage of logos.

Conclusion

So, is the Golden Ratio a myth or truth in logo design? It can indeed be traced in some of the world’s most famous logos, but it is absent in most.

Consider it this way: As a designer, you often face countless choices. When determining the curve of a shape, drawing a symbol, or positioning details, it can be comforting to rely on a rule, like the Golden Ratio.

It’s for this reason (and sometimes probably by sheer coincidence) that the Golden Ratio appears in logo design. In reality, the logos would probably have turned out just as well with slightly different proportions.

—

Read a summary of this article: Should You Use The Golden Ratio In Your Logo Design at Medium.